The Place of Literature on the Great Plains; Or, “There never was an is without a where.”

Photo by Dana Fritz

By Cory Willard, English PhD student, Great Plains Graduate Fellow

Historically, the study of literature has often relegated setting to the background—a stage whereupon the important human stuff takes place. Within the last few decades, however, greater importance has been placed on setting and, specifically, the environment that produces certain literatures. How does literature affect our thoughts and feelings about a place? How does what we learn through artistic expressions like literature affect how we see and act toward the world around us? What role can literature play in addressing the current environmental crises we face both locally and globally? What importance (or lack thereof) do we give to nonhuman life?

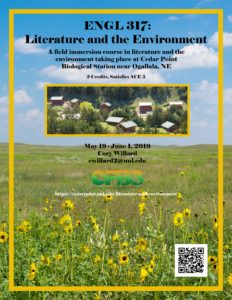

Class poster

These are the types of questions UNL undergraduates attempted to answer during a two-week, immersive field course in literature and environment at Cedar Point Biological Station on the shores of Lake Ogallala, Nebraska. Over the two weeks, students kept nature journals, went on field trips, had intense discussions, and read eight nonfiction books based on the Great Plains to better understand how the place, literature, and their own lives and perspectives are intertwined. Throughout this journey, a quote from Lawrence Buell’s book Writing for an Endangered World became a guiding theme: “there never was an is without a where.”

English 317, “Literature and Environment,” asks students to explore their relationship with nature, our socio-economic relationship with the natural word, and literature’s relationship to the environment. I am not from the Great Plains (I am from Alberta’s Peace River Country where the northwestern portion of the Great Plains gives way to Canada’s Northern Boreal Forest), but my position as a Graduate Fellow with the Center for Great Plains Studies has provided me the opportunity to learn about, intimately connect with, understand, and to teach about the history, literature, and environmental issues surrounding this very special place.

Spotted sandpiper. Photo by Cory Willard

Through a study of eight books we tried to uncover just what makes the Great Plains the Great Plains beyond just their geological formation. We looked at evolution and deep time through Loren Eiseley’s The Immense Journey which was influenced by his field work in the Wildcat Hills. We looked at water issues in Julene Bair’s The Ogallala Road and Doreen Pfost’s This River Beneath the Sky. We looked at agricultural and land-use issues through Dan O’Brien’s conversion of his South Dakota ranch to an ecologically functioning bison operation in Buffalo for the Broken Heart and Ted Genoway’s This Blessed Earth, which was the One Book One Nebraska selection for 2019 and the winner of the 2018 Stubbendieck Great Plains Distinguished Book Prize. Additionally, we read books that added further elements of culture and focused on how we make meaning and shape our sense of place in Ian Frazier’s Great Plains and Stephen R. Jones’ The Last Prairie.

Long-billed curlew. Photo by Cory Willard

Inhabiting the actual place that inspired the literature added new dimensions beyond what a student normally receives in a literature class – an ideal set up when looking at environmental and ecological relationships. The class went on several small hikes and a couple of longer excursions. When reading John Janovy Jr.’s Keith County Journal, we were able to drive the Keystone-Paxton road and visit Ole’s Big Game Steakhouse & Lounge in Paxton and the town of Keystone—locations mentioned in the chapter “Swallows.” Students were able to experience first-hand what Janovy was thinking about when he wrote that “maybe, just maybe, on those windswept grasslands there are lessons to be learned, sights to be seen, subtleties that sharpen the eyes and ears, and most of all relationships between living things that are worthy of [attention].” When reading Stephen R. Jones’ The Last Prairie we were able to visit Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge, a location that features prominently throughout the book. We marveled at carp in shallow wetlands, a garter snake vomiting up a large salamander before escaping through the water, and long-billed curlews (above) which John Janovy Jr. describes as “a mystery bird, the kind of bird that might appear in a Disney real-life adventure film, the kind of bird that makes films like these successful, because it is so far outside the daily experience of every person.”

Cedar Point Biological Station bird release. Photo by Cory Willard.

In addition to reading literature, students were also able to experience and discuss the landscape photography of UNL Professor Dana Fritz and undertake bird netting and banding with Dr. Allison Johnson.

All of these activities highlighted how important a sense of place is to belonging and how the intersection of literature, visual art, and ecology can meaningfully shape how we see and inhabit the world.

Cedar Point Biological Station (CPBS) is UNL’s only full service field campus on the western high plains, and is dedicated to place-based experiential learning and field research. CPBS hosts UNL summer courses and is a site for various research projects from a wide variety of institutions. CPBS includes 950 acres of prairie, tree filled canyons, and facilities located near Ogallala, NE, on the south shore of Lake Ogallala and adjacent to Lake McConaughey.

The CPBS summer field season is May to August, with select events offered into October. All potential new users and persons interested in volunteering at CPBS are always very welcome to contact us. See: http://cedarpoint.unl.edu