Literature on the Great Plains

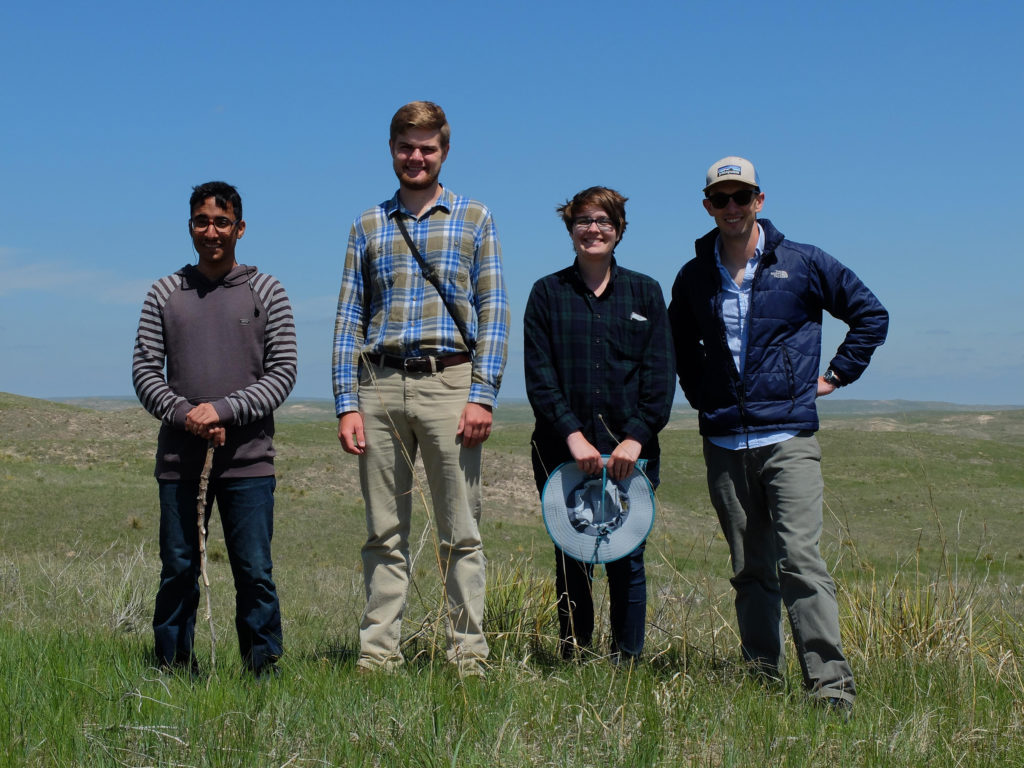

Students at Cedar Point Biological Station

Photos and story by Daniel Clausen, Great Plains Graduate Fellow, UNL English

How does literature influence our understanding of a place? This past May, three UNL undergraduates tried to answer that question as directly as possible. Over the course of only two weeks, they read, discussed, and wrote about eight Great Plains books—all while living at the edge of the Sandhills in Western Nebraska at UNL’s Cedar Point Biological Field Station.

In early May, the weather on the high plains of western Nebraska is variable to say the least. When I drove up a day before students arrived, the road was slick from a thunderstorm the night before. Piles of pea sized hail had washed down the gullies, and were over a foot deep in places. Since the hail was insulated by a layer of duff, you could still pick up a handful of ice a full week later, when the midday temperatures pushed into the upper 80s. By then, several dozen students were paddling canoes and kayaks on Lake Ogallala, and swinging bug nets through long grass. While students such as these in the biological sciences have been coming to Cedar Point for decades to learn to do the field work that drives biology, 2018 marked a first for Cedar Point: a literature class.

Cedar Point Biological Station class

English 317, “Literature and Environment” aims to guide students to think critically about nature. As a graduate fellow of the Center for Great Plains Studies, teaching this class gave me an opportunity to introduce students to a variety of tropes that shape how we tell the story of this particular environment called the Great Plains. Was it raw material waiting to be made productive and civilized by strong pioneer women, as Bess Streeter Aldrich writes in her classic pioneer novel A Lantern In Her Hand? Or do the wild bluffs and birds reveal the wonderful complexity of nature and humanity’s peculiar mixture of insignificance and ecological power, as UNL alumnus Loren Eisley’s The Immense Journey narrates? How might we, beneficiaries of a settler culture, relate to the story of the Cheyenne who once lived in this place—a question raised by Mari Sandoz’s masterful and indicting Cheyenne Autumn? And those other students at Cedar Point—was their pursuit of science as heroic as UNL professor emeritus John Janovy, Jr.’s Keith County Journal presented it to be?

We discussed these questions while hiking, avoiding prickly pear spines. We waded the trickle of the North Platte to find the mouth of Whitetail Creek—a place that had a central role in three separate books. We visited the Crescent Lake Wild Life refuge, an isolated collection of pothole lakes and grassy dunes first made real to the students in the writing of Stephen Jones’ The Last Prairie, who gave us the tools to see its subtle and timeless beauty. We watched bitterns, yellowlegs, ibis, and curlew. We held mud turtles and box turtles. We observed bald eagles and prairie dog towns with resident burrowing owls.

My three students took a risk in heading to Cedar Point. In so doing, they opened not just their minds but their hearts to the effects of these wide open spaces. The long vistas encouraged deep thinking, new possibilities, and generosity even in disagreement, as modeled in Dan O’Brien’s Buffalo for the Broken Heart and Julene Bair’s The Ogallala Road. Which was helpful, since the students could not have been more different: a philosophy and accounting double major from the Sultanate of Oman, a range science major from a farm outside Grand Island, and an environmental studies major from Maryland. But all three came away united by a place, and a set of experiences—exposed out on the prairie, but also deep in their pages of prairie books. And I would bet they will recognize other plains-folk for the rest of their lives.

On the road to Cedar Point Biological Station

Cedar Point Biological Station (CPBS) is UNL’s only full service field campus on the western high plains, and is dedicated to place-based experiential learning and field research. CPBS hosts UNL summer courses and is a site for various research projects from a wide variety of institutions. CPBS includes 950 acres of prairie, tree filled canyons, and facilities located near Ogallala, NE, on the south shore of Lake Ogallala and adjacent to Lake McConaughey.

The CPBS summer field season is May to August, with select events offered into October. All potential new users and persons interested in volunteering at CPBS are always very welcome to contact us. See: http://cedarpoint.unl.edu