Harsh winter affects crane migration

By Jenna Bartja, Adventure Travel Specialist, Nebraska Tourism Commission

This past Monday, March 11, I visited Rowe Sanctuary for the first time to witness the largest gathering of cranes on earth. Each March, the cranes stopover on a stretch of the Platte River between Kearney and Grand Island as part of their annual migration north to summer nesting grounds. March is THE month to see the cranes, with previous counts this time of year averaging 73,600. This year, however, is yielding a different experience.

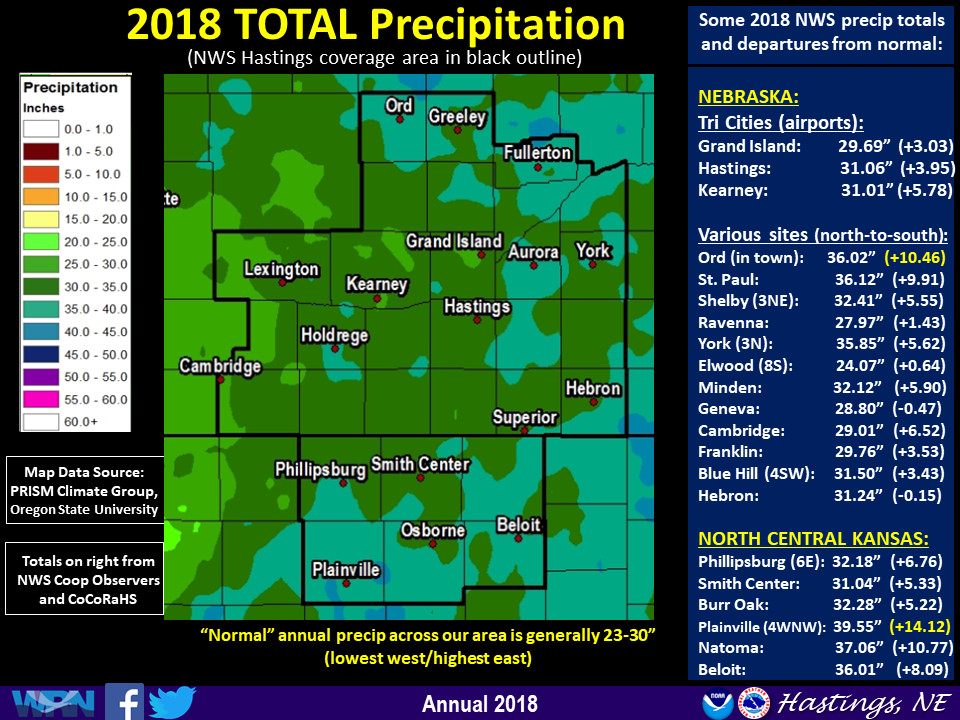

Many counties in Nebraska experienced a wetter-than-average winter, with the tri-cities of Grand Island, Hastings, and Kearney receiving 3-6 inches above average precipitation in 2018, according to the National Weather Service.

This, combined with the prevailing chilly temps, has left the Platte River frozen much later into the season than is typical. The harsh winter has stalled the cranes on their journey as they, like us, have had to face complications from the snow and ice. Perhaps their biggest challenge has been the lack of access to their food sources, trapped beneath snow covered fields, frozen lakes and rivers. Now that the cranes have begun to trickle through the central flyway, in numbers far less than typical for this time of year, experts at both the Crane Trust and Rowe Sanctuary have observed peculiar behavior patterns.

Cranes prefer to roost on isolated sandbars in the center of the Platte River because they offer protection from nighttime predators such as coyotes, foxes, and bobcats not wishing to make the trip into the swiftly flowing waters. The river also offers a supplemental buffet of plant tubers and aquatic invertebrates for the cranes to feast on in addition to their staple of waste corn from surrounding crop fields. A frozen river cannot offer the same protection, nor can it provide the additional sustenance.

Nonetheless, we observed the cranes, out of habit, retreating to the Platte at dusk. They resorted to lying low on the iced-over river, perhaps in an effort to protect themselves from the even colder surrounding air and bitter wind-chill. A couple of coyotes were spotted scouting the far shoreline. Even bald eagles congregated on the ice and were seen in large numbers (I counted 19 at their highest concentration!) overlooking the river from the surrounding cottonwood trees. Primarily scavengers, they don’t like working too hard to secure their meals but they, too, have endured the long winter and are perhaps, as one of the Rowe volunteers offered, opportunistically lingering awaiting the possibility of scoring an injured crane as easy prey.

As the flocks began swarming over the protected blinds, we noticed that most of them were mixed species. I looked to the volunteers for an explanation. They told me that the mixing of flocks is not uncommon, but this year they were impressed by the quantity and variety in the flocks, which were likely driven together by the series of winter weather events delaying them all on their journey. Smaller flocks were more likely to contain singular species, but the larger hoards contained a spectacle of Sandhill cranes, Canada geese, snow geese, greater white-fronted geese, and merganser ducks. The sky became a cacophony of bugles, trills, and honks, growing louder all the time in harmonization with the impending darkness.

As I walked through muddy, icy slush back to my car, I reflected over the last few hours spent in the blind. It was a truly sensational experience to watch these birds brave such unforgiving conditions, being driven north by an unfathomable force of nature and instinct. Life goes on, harsh winter or no.