3 billion birds: What about the Great Plains?

By Katie Nieland, Center for Great Plains Studies

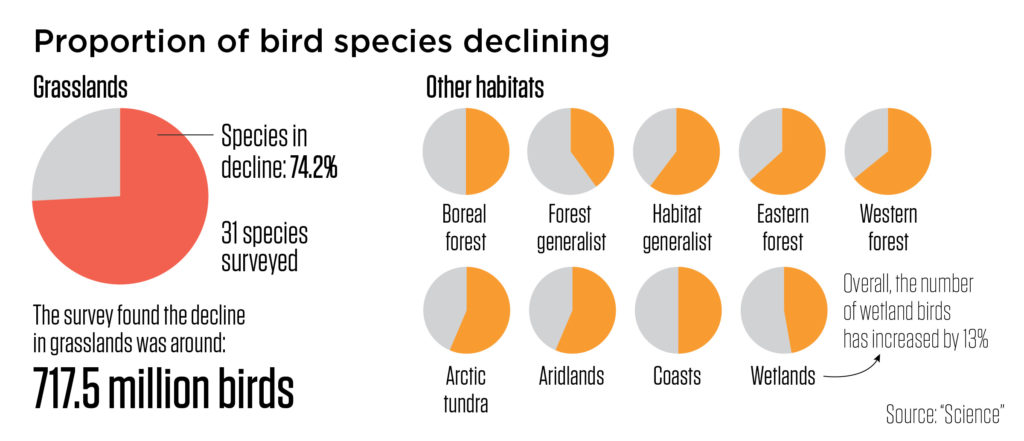

New research in Science about the loss of 3 billion birds has made headlines across the nation. Using bird surveys and weather radar, scientists from several organizations report a net loss of 29% of individual North American birds since 1970. Ramifications could be severe, since birds are often a species that indicates the environmental status of an ecosystem.

How does our region fit into that picture? Let’s zoom in on the Great Plains, which is roughly equivalent to the report’s “grassland” area. Compared to other North American habitats, grassland species saw the largest drop in individual bird numbers. It also has the largest proportion of species in decline: 74.2%.

Great Plains researchers have been concerned about grassland birds long before this research. For example, six songbird species only found in this region have declined by 65-94% since the 1960s.

Photo credits: Baird’s sparrow (USFWS Mountain-Prairie), Cassin’s sparrow (Bill Bouton), chestnut-collared longspur (USFWS), lark bunting (Andy Reago & Chrissy McClarren), Sprague’s pipit (Logan Kahle), McCown’s longspur (Dominic Sherony).

The Great Plains as bird habitat

This semi-arid grassland features three prairie types (short grass, mixed, and tall grass), which is dotted by various forbs and shrubs. Trees usually occur around water sources. The low number of trees compared to a forested area means there are fewer vertical places for birds. In a forest, birds can nest and forage on the ground, shrubs, or at various tree heights. Fewer vertical niches on the prairie means birds may be found at lower levels, even nesting on the ground, which makes them more vulnerable to habitat disruption, destruction, and predators.

The ecosystem itself is harsh, with variable weather including winds, storms, cold snaps, and drought. Bird populations on the Great Plains are dominated by relatively few local, year-round species (somewhere around 30), but a much larger cohort of migratory visitors. The endemic birds, found only here, are primarily short grass to mixed-grass species (Knopf, 1996).

The central flyway is another complex factor for bird life in the Great Plains. Migratory birds who use this north-south route across North America rely on marshes, wetlands, and rivers for spring and fall journeys. Draining or channelizing these wet habitats puts some of the continent’s most threatened birds at risk, including the whooping crane and snowy plovers.

Challenges for Great Plains birds

Besides habitat harshness, what else is specifically happening on the Great Plains that could contribute to the largest loss in any habitat category?

Besides habitat harshness, what else is specifically happening on the Great Plains that could contribute to the largest loss in any habitat category?

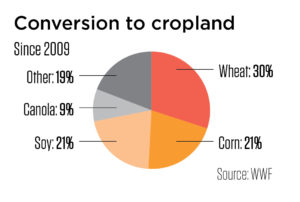

In 2018, 1.7 million acres of grassland were converted to cropland. And while some bird species do well on agricultural lands, many do not. Only about half of the Great Plains’ original grasslands remain, and only a tiny portion of it is tallgrass prairie. While most agricultural land was plowed by 1920, recent plow ups continue as more marginal lands are converted due to crop prices and energy extraction. For many birds, monocrop agriculture means less ecosystem diversity, fewer food sources, and fewer places to nest.

The conversion of prairie to agricultural lands has a long history. Changing technology during the 20th Century meant fewer pastures were needed for milk cows, horses, and sheep. Refrigeration, tractors, and textile innovations meant these pastures could be used for row crops. Innovations in fertilizer and genetics made it easier to grow on marginal lands, converting more land to agricultural uses (Powell, 2015).

Grassland birds tend to avoid roads and other signs of human life. The recent uptick in energy extraction in the region may further fragment and reduce habitat quality (Thompson et al., 2015).

The Future of Great Plains birds

Not all regional species are in decline: ducks, snow geese, Canada geese, and some other game birds have been specifically targeted for conservation efforts with success in sustaining and growing populations. Sandhill crane populations are also growing, with specific habitat management creating an attractive environment for their spring migration stop on the Platte River.

Saving or restoring prairie lands in the Great Plains depends on cooperation with landowners, since private owners hold around 95% of the land (Sieg et al.). Habitat protection and development depends on partnerships between public and private entities and economic opportunity for landowners. Conservation on private land can only be accomplished it if compares favorably with other ways the land could be used (Powell, 2012). Nature tourism is one way to tip the scales in favor of conservation. If landowners can make a profit through nature tourism, there is more incentive to maintain the land’s natural state. Other incentive programs, including conservation easements, can also set aside land for habitat. Though a small percentage of the area, public lands are also key, especially when they serve to connect habitats into corridors.

Three billion birds is big news, and the Great Plains’ population certainly is at risk. It will take partnerships, investment, time, and research to protect and restore habitat and the birds that live there.

* * *

For more information about plains birds, see the Center for Great Plains Studies newest book in the Discover the Great Plains series: Great Plains Birds by Larkin Powell.

References

Central Flyway. (2015, December 16). Retrieved from https://www.audubon.org/central-flyway.

Knopf, F. L. (1996). Prairie Legacies – Birds. In Prairie Conservation: Preserving North America’s Most Endangered Ecosystem (pp. 135–148). Island Press.

Powell, L. A., 2012. Common–interest community agreements on private lands provide opportunity and scale for wildlife management. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 35.2: 295–306.

Powell, L. (2015). Hitler’s Effect on Wildlife in Nebraska: World War II and Farmed Landscapes. Great Plains Quarterly, 35(1), 1–26. doi: 10.1353/gpq.2015.0003

Rosenberg, K. V., Dokter, A. M., Blancher, P. J., Sauer, J. R., Smith, A. C., Smith, P. A., … Marra, P. P. (2019). Decline of the North American avifauna. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw1313

Sieg, C. H., Flather, C. H., & McCanny, S. (1999). Recent biodiversity patterns in the Great Plains: Implications for restoration and management. Great Plains Research, 9(Fall), 277–313.

Thompson, S. J., Johnson, D. H., Niemuth, N. D., & Ribic, C. A. (2015). Avoidance of unconventional oil wells and roads exacerbates habitat loss for grassland birds in the North American great plains. Biological Conservation, 192, 82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2015.08.040

World Wildlife Fund. (2018). The Plowprint Report: 2018.